Introduction to graphic medicine

Most people are unfamiliar with the term "graphic medicine" when I use it. Let's begin by outlining what graphic medicine actually is.

What is graphic medicine?

According to the definition coined by Dr. Ian Williams, the study of graphic medicine focuses on how the comic book medium and the healthcare discourse interact, broadly speaking. Although we talk about graphic medicine, it is quite an oversimplification; other fields related to medicine, such as public health or nursing equally belong under this category. That is why I often refer to this field as graphic public health. According to Dr. Williams, the term "medicine" encompasses more than simply the practice of medicine and applies also to the therapeutic and healing potential of comic books.

It's a relatively new discipline, academically speaking, however, already very prolific; there are many titles that have been published especially over the last decade, and comics gradually appear in university classrooms. At the same time, there is a great unfulfilled potential of studying comics and their effectiveness when it comes to communicating ideas in the healthcare field.

One of the milestones for the discipline of graphic medicine was undoubtedly the publication of the book Graphic Medicine Manifesto in 2015. The book brings us closer to the origin of the field, mentions some of the key authors and titles that you may be interested in checking out, and provides more information regarding how comics can be beneficial in discussing and learning about healthcare issues.

Advantages of comics as a medium

It is difficult to talk about graphic medicine without first highlighting the benefits of comics as a medium.

First of all, comics are based on storytelling traditions. And storytelling, at its core, is about connection and communication, and is a powerful tool for conveing messages through shared human experience. We learn more effectively when we have a chance to listen to stories that engage us and make us reflect.

Secondly, comics are inclusive - they speak to diverse communities: individuals of all ages, from all walks of life, and give voice to those whose perspectives are often neglected, such as indigenous communities, immigrants, or, in the field of medicine, doctors in training or caregivers.

What is more, through the use of visuals, comics are an alternative to verbal communication as combining pictures and text enhances understanding and can help us comprehend and deal with complex subjects. This is especially relevant when educating patients, as for many, medical jargon can pose challenges. In addition, visuals improve recalling. They help us remember things better. In medical education, for example, studying illustrations of human body is essential in understanding how the various structures of our bodies that are not visible to the naked eye are organized and how they function. Imagine studying anatomy entirely from a textbook with no images at all. It seems like it would be a quite an unpleasant experience.

How can we use comics to educate others?

The first article on comics in medical education that was published in a major medical journal in 2010 was Graphic Medicine: Use of Comics in Medical Education and Patient Care by Green and Myers.

The article as well as studies published afterwards highlighted how comics in medicine can be particularly useful for promoting public awareness and literacy regarding various physical and mental health issues. During the pandemic, we’ve seen more illustrations showing how to wash hands properly or providing advice on how to act during a pandemic in a more inventive way, like these comics by Sami Lee and Malaka Gharib:

Comics can also give us insights into different aspects of illnesses and show us what it’s really like to suffer from a particular disease. This is not only crucial for developing empathy, but also important in clinical practice to educate health professionals about the various ways that diseases can be manifested in different patients. As an example, Georgia Webber, a Canadian artist, wrote a graphic novel titled Dumb about her experience losing voice for about six months and how it affected her life. She discusses the challenges she faced when communicating with others, how she was misdiagnosed, and how she managed to support herself during that difficult period.

Dumb by Georgia Webber, 2018

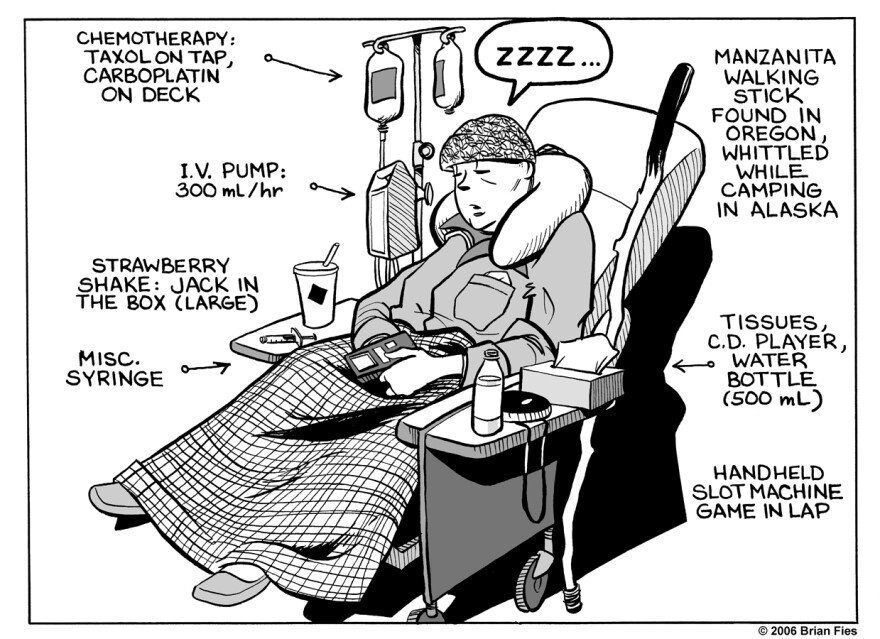

When we share our experience of health and disease, it can also massively help others that suffer from the same condition, petting them know that they are not alone in their struggles. Brian Fies’ Mom’s Cancer, where the author chronicled his mother’s illness and life after remission, was published in 2006. Before that, however, when his mother was diagnosed, Fies started posting short comic strips on his website , which helped him amass a large community that was following his mother’s journey. He also received a lot of messages from cancer patients or their loved one expressing gratitude for his work.

Mom’s Cancer by Brian Fies, 2006

Comics can also help us understand disability better: Here we’ve got a graphic novel by Kaisa Leka, I Am Not These Feet. Kaisa was born with deformed feet and suffered from arthritis. As she got older, she decided to get both her feet amputated. The book follows her recovery and new life with prosthetic feet.

I’m Not These Feet by Kaisa Leka, 2003

Let’s not forget about mental health. Alfonso Casas in his graphic novel, MonsterMind, records his battle with depression during the pandemic, by portraying each of his fears and anxieties as monsters that accompany him every day, making them visible and tangible, and thus acknowledging their presence, which helped with his recovery.

Monstermind by Alfonso Casas, 2022

The last significant category of medical graphic novels I'd like to bring up is those that tackle the challenges that health professionals face every day in their work, but which are rarely discussed or at the very least don’t receive enough attention. Taking Turns by MK Czerwiec started my interest in graphic medicine. Czerwiec recalls her stories from the 1990s, when she worked as a nurse at an HIV/AIDS unit in during the height of the AIDS epidemic in Chicago. There she opens up about the mental toll that losing patients and friends had on her.

Taking Turns: Stories from HIV/AIDS Care Unit Unit 371 by MK Czerwiec, 2017

Another good example would be a comic book by Dr. Ian Williams, the founder of the graphic medicine movement. In The Bad Doctor, we follow the life and work of a fictional character, Dr. Iwan James, a physician who, while caring for his patients, struggles with his own mental health problems, such as obsessive-compulsive disorder.

The Bad Doctor: The Troubled Life and Times of Dr. Iwan James by Ian Williams, 2015

I'd like to briefly discuss the potential of comics beyond medicine to wrap things up. Graphic novels have the ability to raise pressing questions that are frequently overlooked in research and education. I know that I probably wouldn’t read on my own about the Vietnam war, life in Iran during the Islamic revolution, the accounts of people suspected of terrorism and sent to Guantanamo, or the internment camps to which people of Japanese descent living in the U.S. were sent during World War II if it hadn’t been for comic books on these subjects. Because comic books have this wonderful capacity to take difficult topics, such as illness, disability, war, racism, social injustice, and make them accessible, inviting reflection and focusing on shared human experience regardless of our differences, and allowing us to learn at our own pace.

The Best We Could Do by Thi Bui, 2017

Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi, 2007

Guantanamo Voices by Sarah Mirk, 2020

They Called Us Enemy by George Takei, 2019